The Revival of Freaknik, its new documentary, and Black social life in the 90s

Once again, we're worried about the wrong sh*t. (TW: S*xual Assault)

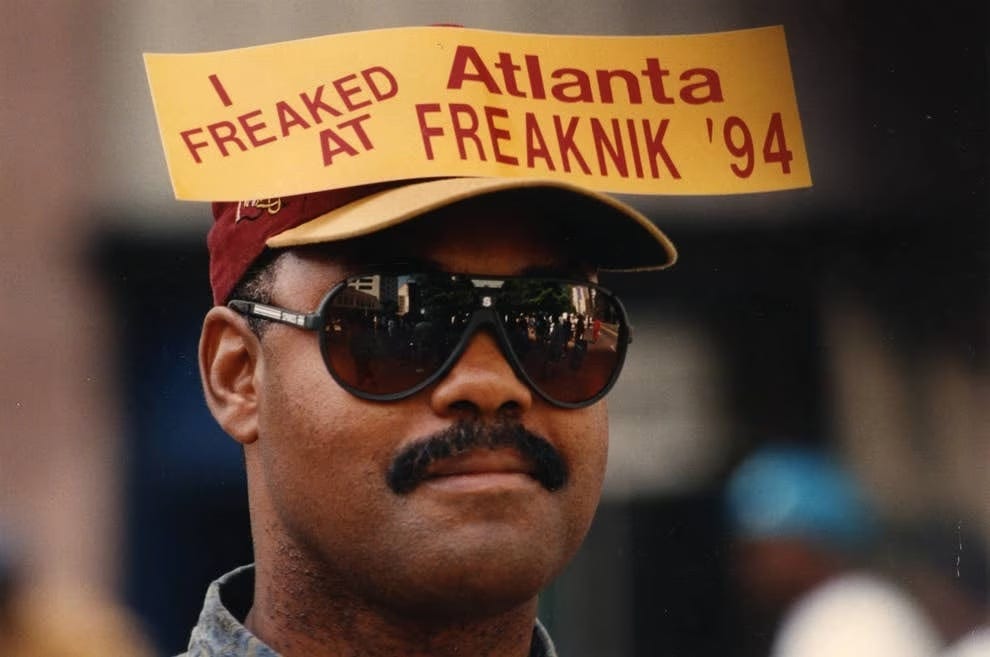

Source: Johnny Crawford featured in Yahoo News

Last week, Variety dropped exclusive news: Hulu is set to release a documentary on the historic 90s spring break experience, Freaknik. In summary, this original documentary, titled “Freaknik: The Wildest Party Never Told,” details what was considered the ULTIMATE HBCU spring break experience in the 80s and 90s. There has since been a barrage of other news stories, including these ones by Decider and Complex. There has been plenty of buzz on social media about the potential contents of the documentary, which I can’t find a reliable release date for. Many have posted about their concerns about being featured as past attendees, but the uninteneded consequence of the doc is going to be that it is going to expose how unready we still are to deal with conversations about sexual assault and violence against Black women within the Black community.

A brief run down: According to theGrio, from the mid 80s through mid 90s, Freaknik grew to 250,000+ attendees at its peak (5x larger than the largest Black music festivals today). Started on Spelman’s campus under the moniker “Freaknic”, inspired by then popular music and a play on the title picnic, the festival quickly grew to an experience boasting hundreds of thousands of attendees from several countries. Within a few short years, Spelman’s president Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole had barred Spelman students from promoting the event, and party promoters who weren’t affiliated with the AUC had renamed the event “FreakniK” in a move away from the college student creators’ original efforts. By 1998, the Atlanta Committee for Black College Spring Break told AP that the spring break experience had become a huge public safety concern — including rampant sexual assault and violence against women, as well as fire and EMS not being able to reach injured attendees or transport them to nearby hospitals. In 2010, Freaknik was banned by Atlanta’s then mayor, but revived almost a decade later with a family friendly rebrand.

Source: Marlene Karas | AP

Since the news dropped, the internet has been in a tizzy over the “Freaknik documentary”. I’m personally already side eyeing the title, cuz “never” told to who? Many of us have heard stories about how fun and wild Freaknik was, whether we have a parent or auntie/uncle who attended or not. But I digress. Folx have been swirling, posting clips of some of the most salacious activities to take place on record. Lots of booty shaking, loud music, camcorders — expected for young people who imaginably didn’t think footage of their experiences would ever resurface. I’ve been watching the buzz over the last few days about the doc, and had seen so much commentary on the potential of what was included in it that I didn’t even know the title of it until I sat down to write this.

In my own social media echo chambers, I’ve seen Professors Kwame Jeffries and Marc Lamont Hill publicly share that they attended Freaknik while they were college students in Atlanta, and how great the parties were. I’ve seen tiktoks of auntie aged Black women, sharing how nervous they were that they might appear in the doc now that they are grown and have careers. And I’ve seen a lot of tweets like this and this, and even an Instagram story featuring a screenshot of a person asking their parent if they’d attended Freaknik at one point. Folx are shook at the possibility they’d see their mothers, aunties, sisters, or family friends participating in Freaknik festivities.

Tweets and tiktoks in response to the news have come to similar consensus: we are ready to police how young Black women behaved once this documentary comes out. And after seeing this video on twitter yesterday, I knew I was right in being unafraid to see any woman I knew partying at Freaknik. (Please note: people featured in the video are justifying r*pe and sexual assault.) I personally don’t care to comment on how hard young black folx partied prior to our current conceivable version of the internet even existed. But I do think our concern with how Black women were acting at Freaknik is misdirected.

We should be deeply concerned whether or not we will see men that we know and/or care about perpetuating violence against Black women, including s*xual assault on camera, and what it means for ongoing conversations about gender based violence in a post #MeToo world.